Heijing lies in a deep valley, rose-tinted mountains steeply rising to both sides. Along the river, quiet in winter, but roaring in summer, is only space for a single narrow road. Most houses lie up from the road, only reached by cobbled footpaths. There is little land suitable for farming. Heijing seems an unlikely place to build a town.

Yet for many centuries Heijing was amongst Yunnan's richest towns. Founded in the Han Dynasty two millennia ago, even Marco Polo, the 13th century Venetian traveller, knew the place - for Heijing produced Yunnan's most precious good: salt.

They have brine-wells in this country from which they make salt, and all the people of those parts make a living by this salt. The King, too, I can assure you, gets a great revenue from this salt.

Heijing's salt lies deep in the mountains. Yet as rain percolates through the moountains, it passes through the salt deposits, slowly washing out the salt. As brine, water saturated with salt, it reappears in wells just above the river's waters. But to tap into wells commercially, miners had to dig deep shafts into the mountains and bring the waters to the surface with simple pumps. Hundreds of shafts still dot the mountains around Heijing. They are monuments to the sweat of generations.

On the surface the salt was boiled in vats, to crystallize and purify it. Yet whatever effort was spent: Heijing's salt always had a black hue to it. The black salt gave Heijing its name: "Black Salt Well".

From Heijing the salt travelled all over central Yunnan, supplying Kunming and the east. Dali, in the west, received its salt from Yunlong, while the northeast was closer to the wells at Zigong. Yunnan's south received its supplies from near Mojiang. Salt was big business for the caravaners of Yunnan.

But it was not the porters who grew rich on salt. China had early discovered that salt was an easy way of collecting a head tax, particularly in a province that was little under central control. Salt production was in the hands of a few salt merchants who directed the mining and the caravans. They and the officials in charge of collecting the salt tax made small fortunes.

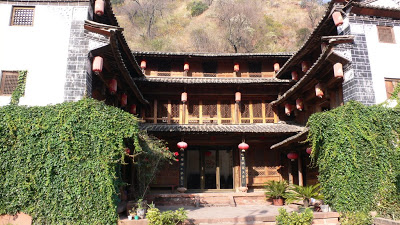

The salt revenues allowed them to build splendid houses. Many, not all of them, have survived the upheavals the last century brought. Some are today protected, yet many more remain crumbling, threatened by collapse.

On Heijing's western side, up on the mountain to catch the early morning sun, is the Wu family mansion 武家院, preposterously built in the shape of the Chinese character wang 王: king. It claims 108 rooms: a propitious number. Another example of Qing architecture is the Bao home 包家院, with a splendid gate and intricately carved stone foundations.

But Heijing's gentry was not ungrateful. Many temples dot the town. The largest, Feilai Temple, overlooks the town from the west. In town, the large Confucian temple, the Wenmiao 文庙 has beautiful stone sculptures on the eastern and western walls. Today it is a primary school.

Today, there is little business in Heijing. Yet still a salt factory survives — a modern one, pumping out the brine with power, destilling and purifying the salt. It is just another chapter in Heijing's long history.

Slideshow

Click to see more