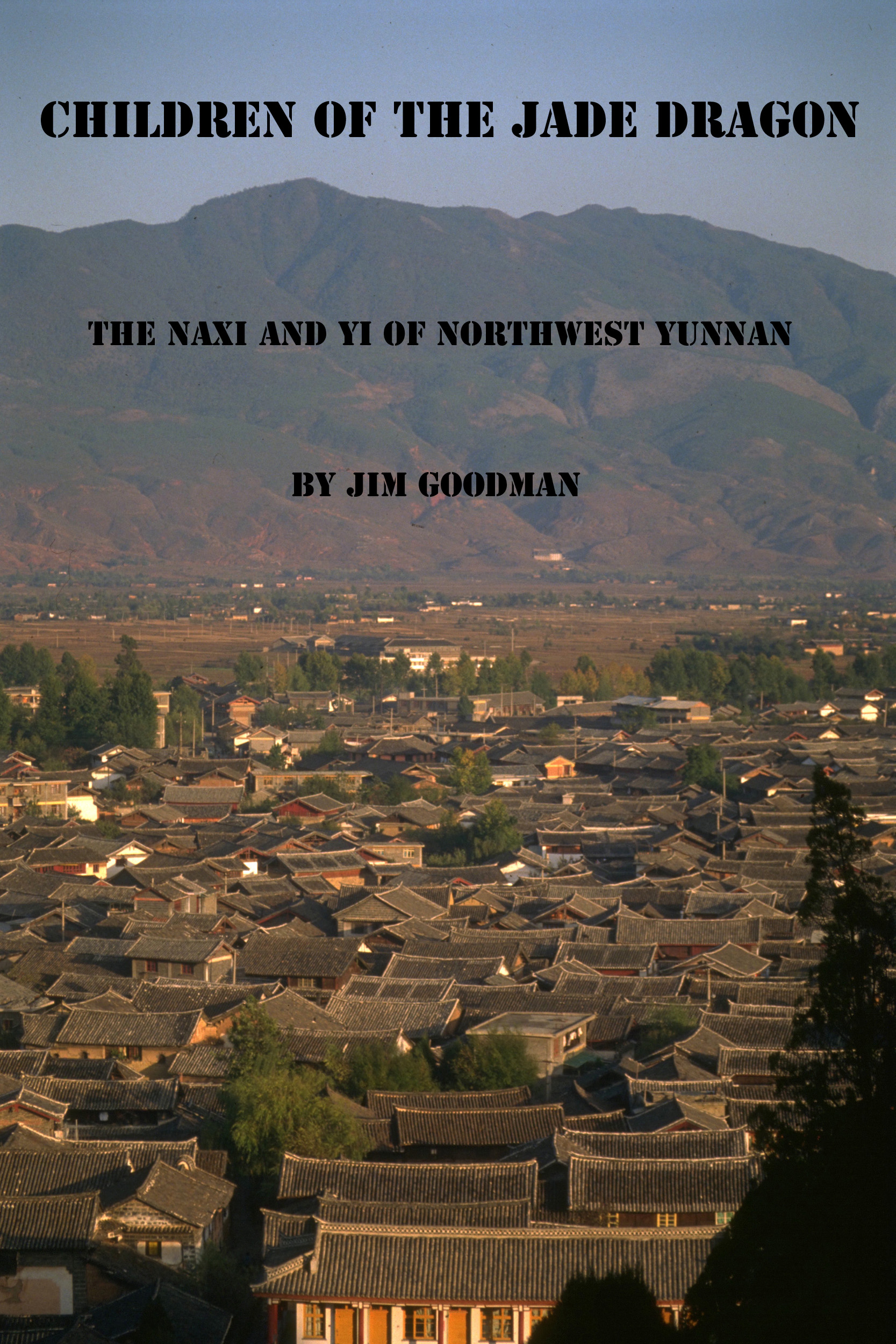

Dayan, the old town of Lijiang, cast its spell on me in the summer of

1992, on my first-ever trip to China. Because of its size, antiquity,

layout and organization it was strongly evocative of Bhaktapur, Nepal,

where I lived for several years in the 1980s. I quickly became

fascinated not only by Lijiang and the Naxi, but also by their

neighbours the Yi, Mosuo and Tibetans, of both Lijiang and Diqing

Prefectures. Over the following four to five years I made research

excursions to northwest Yunnan about every three months, out of my home

base in Chiang Mai, Thailand. I more or less completed my studies of

the area by the end of 1997 and moved on to explore and research other

parts of Yunnan. By then Dayan had begun to recover from the earthquake

of the previous year. It had also been newly listed as a World

Heritage Site, an honour it certainly deserved, for it was one of the

very last traditional urban entities left in southwest China.

The hardcover edition of this book came out at the end of the decade. Dayan had already begun its new incarnation, not as a preserved traditional city, like Bhaktapur, but transformed into an idealized version of itself, re-designed as a tourist hotspot. Nowadays, twenty years after my initial visit, scarcely a single building remains unchanged; rebuilt in the traditional style, but fancier, bigger and with more decorative elements and non-traditional picture windows facing the street. Others, such as the Mu Family Palace and various street arches, have been added. Basically, only the paving stones have remained intact. Nearly all of the original Naxi population has moved out and every building formerly a residence has been re-made into an establishment catering to the tourist trade—guest house, restaurant or souvenir shop—run by outsiders. This updated version of the book required me to change the tense of the verbs used in describing life in the old town.

But I have not tried to detail the course of changes in Dayan. My account of the old town stands as the last description of a Dayan that has ceased to exist just as has the Dayan described by Joseph Rock and Peter Goullart. Yet the sections on Naxi culture, history and traditions is just as valid as in the mid-90s and Naxi life in the countryside has been far less affected by modernisation and the growth of tourism. Similarly, Yi life and culture has also been less transformed. Ninglang is a bigger city, with a modern-style shopping mall among the additions, but it is barely more than a tourist stopover en route to Lugu Lake and the villages in the mountains, where most Yi live, rarely entertain non-Yi guests. While the parts of this book dealing with Dayan are an historical record of a town that no longer exists in the form in which it is described, the facts and observations reported elsewhere herein are still valid for virtually every place beyond the city of Lijiang itself. Moreover, ethnic consciousness has not abated in the last two decades. The people are still proud to be Naxi and Yi.

The new edition of Jim's book is now available for the Kindle on Amazon.

Jim "Black Eagle" Goodman's Blog